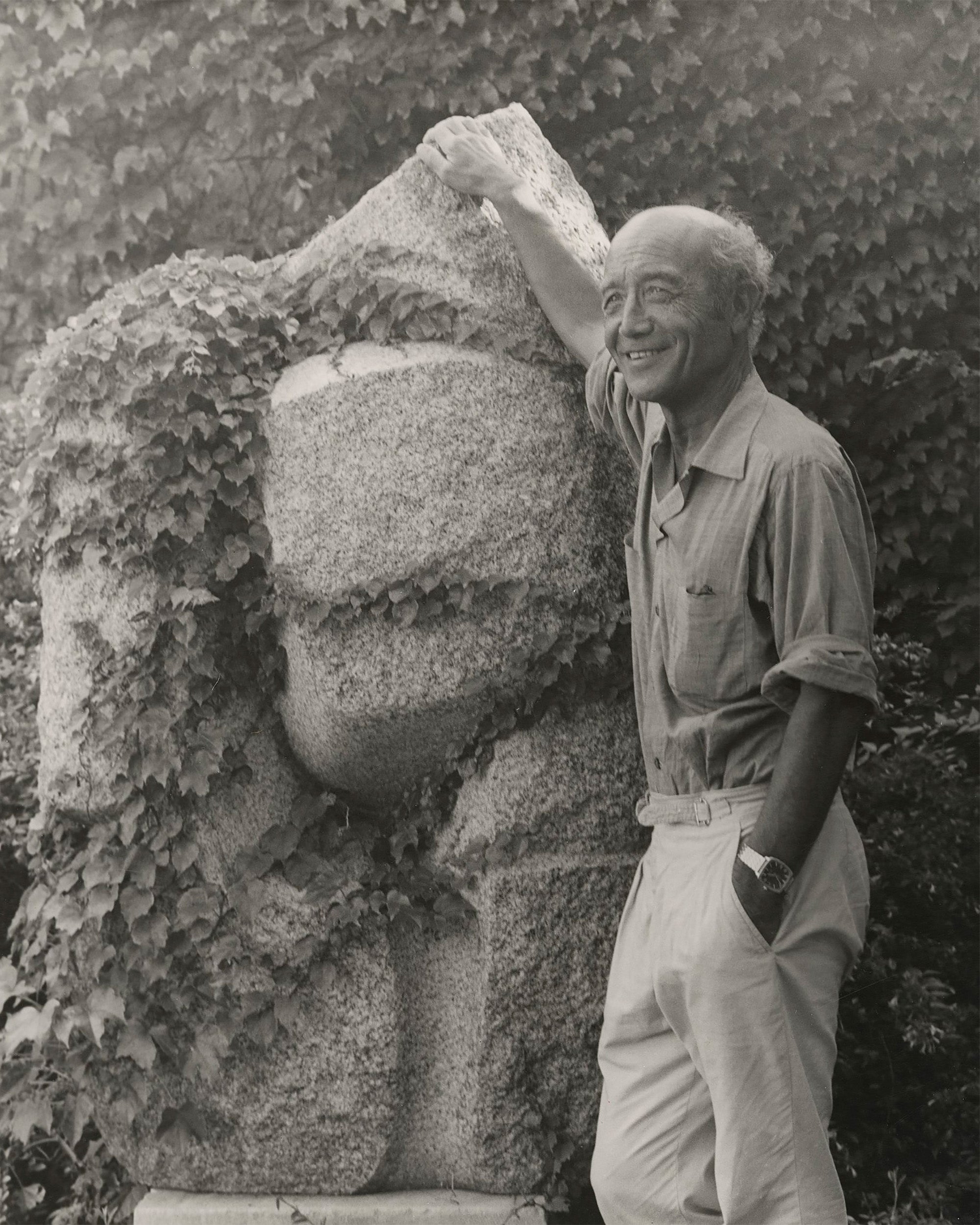

To coincide with our new collection, we’re celebrating history’s Emotional Utilitarians. Designer-makers who committed themselves to the very plainly functional, with a touch of romanticism. Donald Judd is an archetype, with as much of an interest in what makes art art as what makes a chair a chair. Our Untitled frame draws as much from his modular designs and iridescent colour as his approach to the very plainly practical.

‘Rather than making a chair to sleep in or a machine to live in, it is better to make a bed.’ That’s exactly what Donald Judd did when he bought his studio on New York’s 101 Spring Street in 1968. He arranged six planks of wood laterally, raised one inch above the floor, and placed a mattress in its centre. That night, he slept deeply, surrounded on all sides by his art.

Donald Judd might be considered by many to be the very opposite of the Emotional Utilitarian. His oeuvre is composed mainly of sculpture – or to use his preferred term, ‘specific objects’ – which eschew both metaphor and functionality. They simply exist, standing defiantly in the face of utilitarianism.

But Donald was also drawn to the very plainly functional. It’s only the Emotional Utilitarian who will choose to make their home in a space like 101 Spring Street, used exclusively for industrial manufacture for the preceding century. In his life there, and subsequently in Marfa, Texas, he began to make furniture – at first for himself, to resolve his personal struggles in finding pieces fit for purpose, and thereafter to sell in limited collections.

Donald Judd might be considered by many to be the very opposite of the Emotional Utilitarian. His oeuvre is composed mainly of sculpture – or to use his preferred term, ‘specific objects’ – which eschew both metaphor and functionality. They simply exist, standing defiantly in the face of utilitarianism.

But Donald was also drawn to the very plainly functional. It’s only the Emotional Utilitarian who will choose to make their home in a space like 101 Spring Street, used exclusively for industrial manufacture for the preceding century. In his life there, and subsequently in Marfa, Texas, he began to make furniture – at first for himself, to resolve his personal struggles in finding pieces fit for purpose, and thereafter to sell in limited collections.

This is the key distinction in Donald’s world of making. His furniture and art are fundamentally composed in the same language of modularity, but he was careful to ensure they were never considered within the same sentence.

In 1993, he wrote an essay that reads as a manual for the Emotional Utilitarian, entitled ‘It’s hard to find a good lamp’.

‘The art of a chair is... partly its reasonableness, usefulness, and scale as a chair.’

The chair is its own thing. Defined by its chairness. Donald’s most successful chair, the Chair 84, is an incredibly chair-y chair. He created its many variations – rectangular sheets of wood, arranged carefully in perpendicular formation – for his children. When painted, one can’t help but feel a flutter at their monochrome beauty.

A utilitarian object, finding beauty in its simplicity. To some, it's straight sides and harsh angles were not indicative of good design. But Donald was vehement in his response: 'Rather than making a chair to sleep in or a machine to live in, it is better to make a bed.'

A utilitarian object, finding beauty in its simplicity. To some, it's straight sides and harsh angles were not indicative of good design. But Donald was vehement in his response: 'Rather than making a chair to sleep in or a machine to live in, it is better to make a bed.'

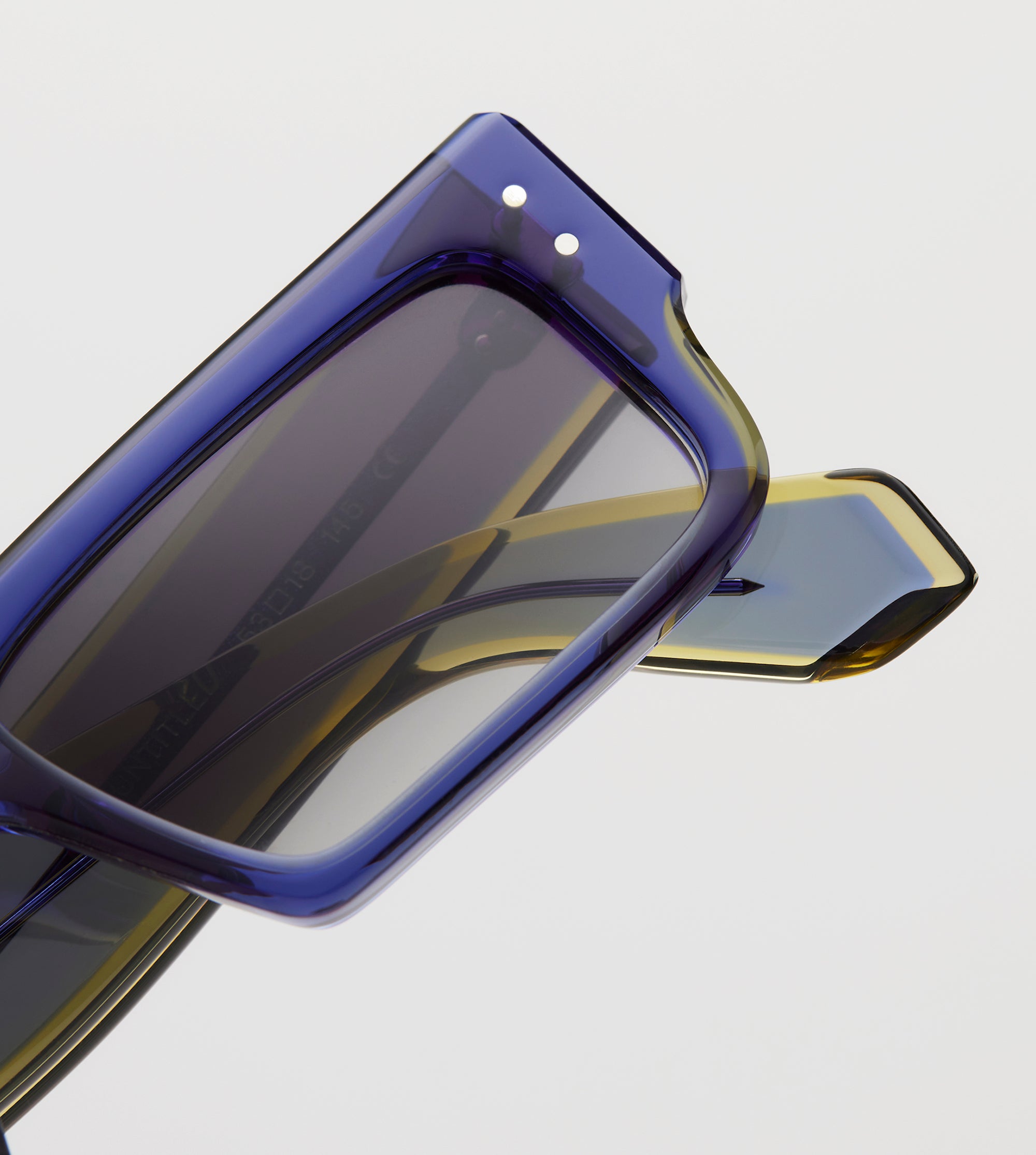

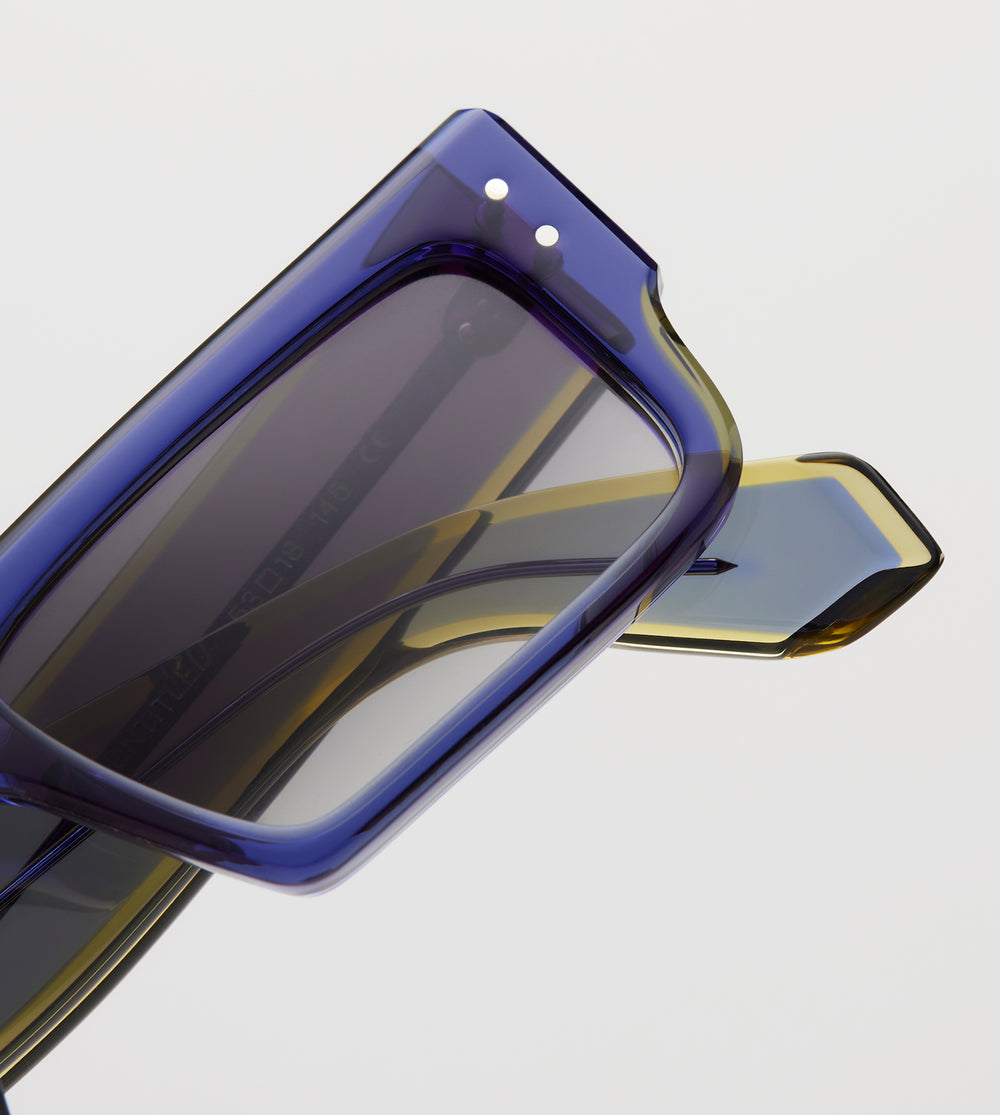

Untitled

A frame that speaks for itself

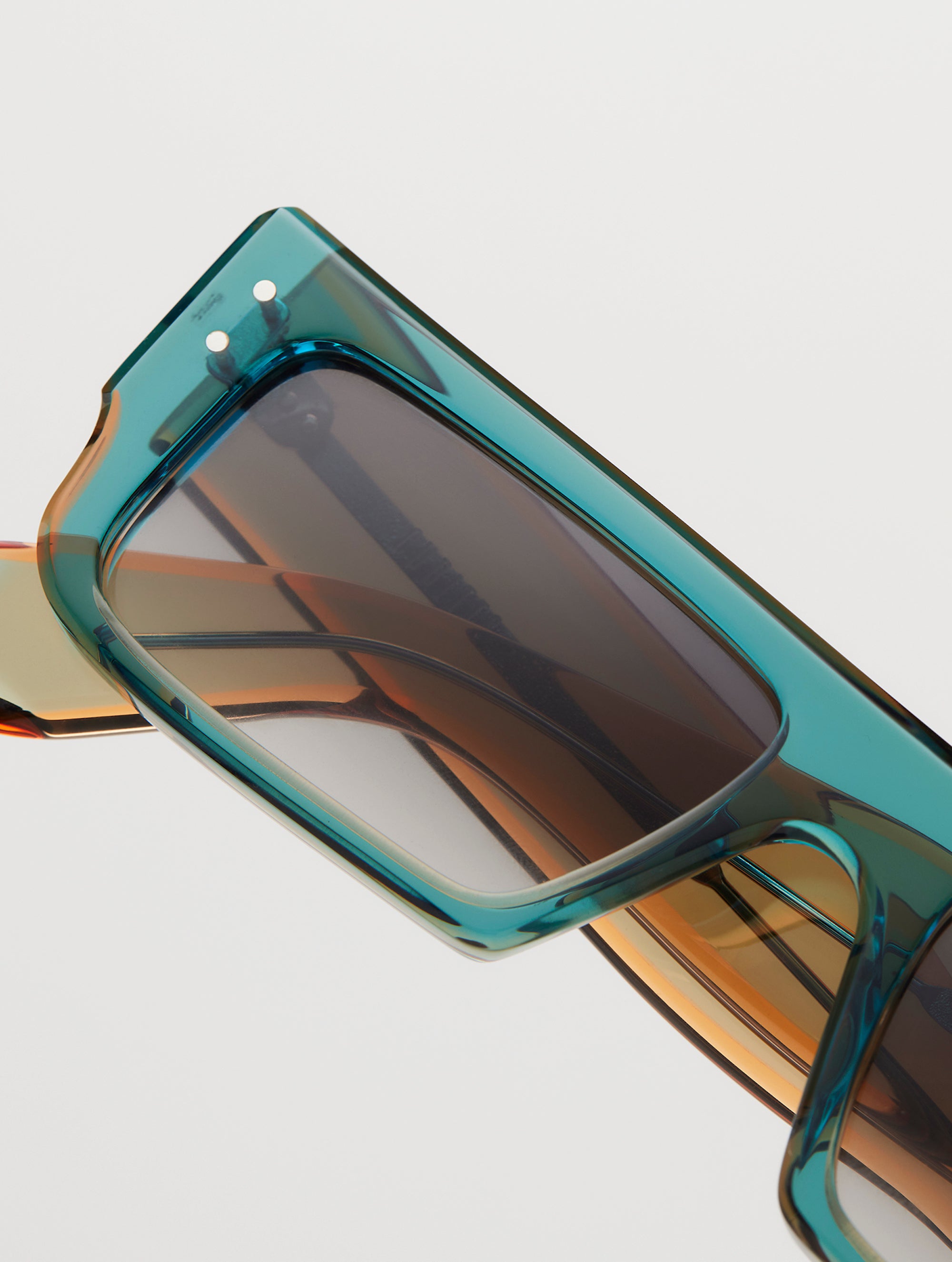

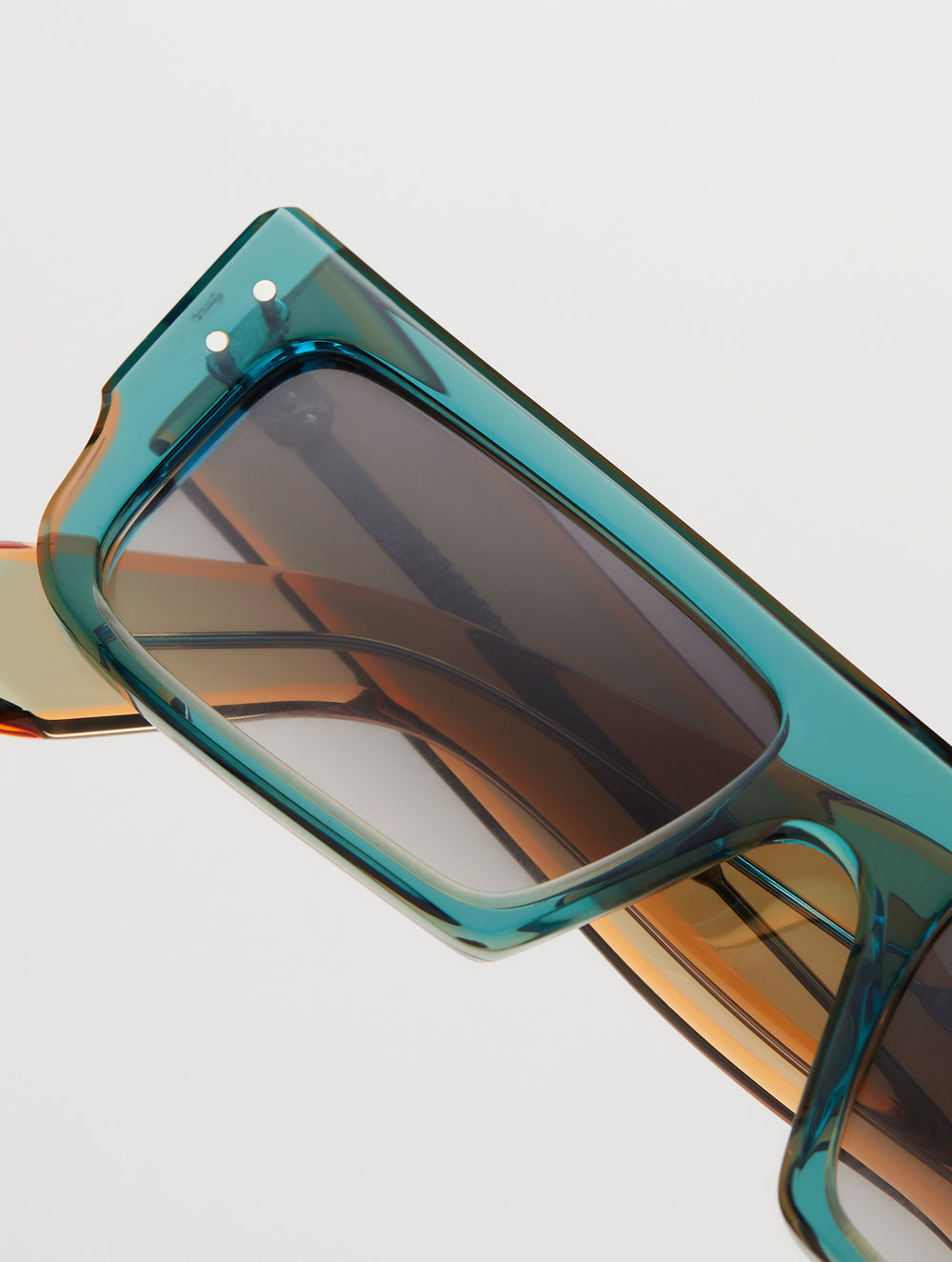

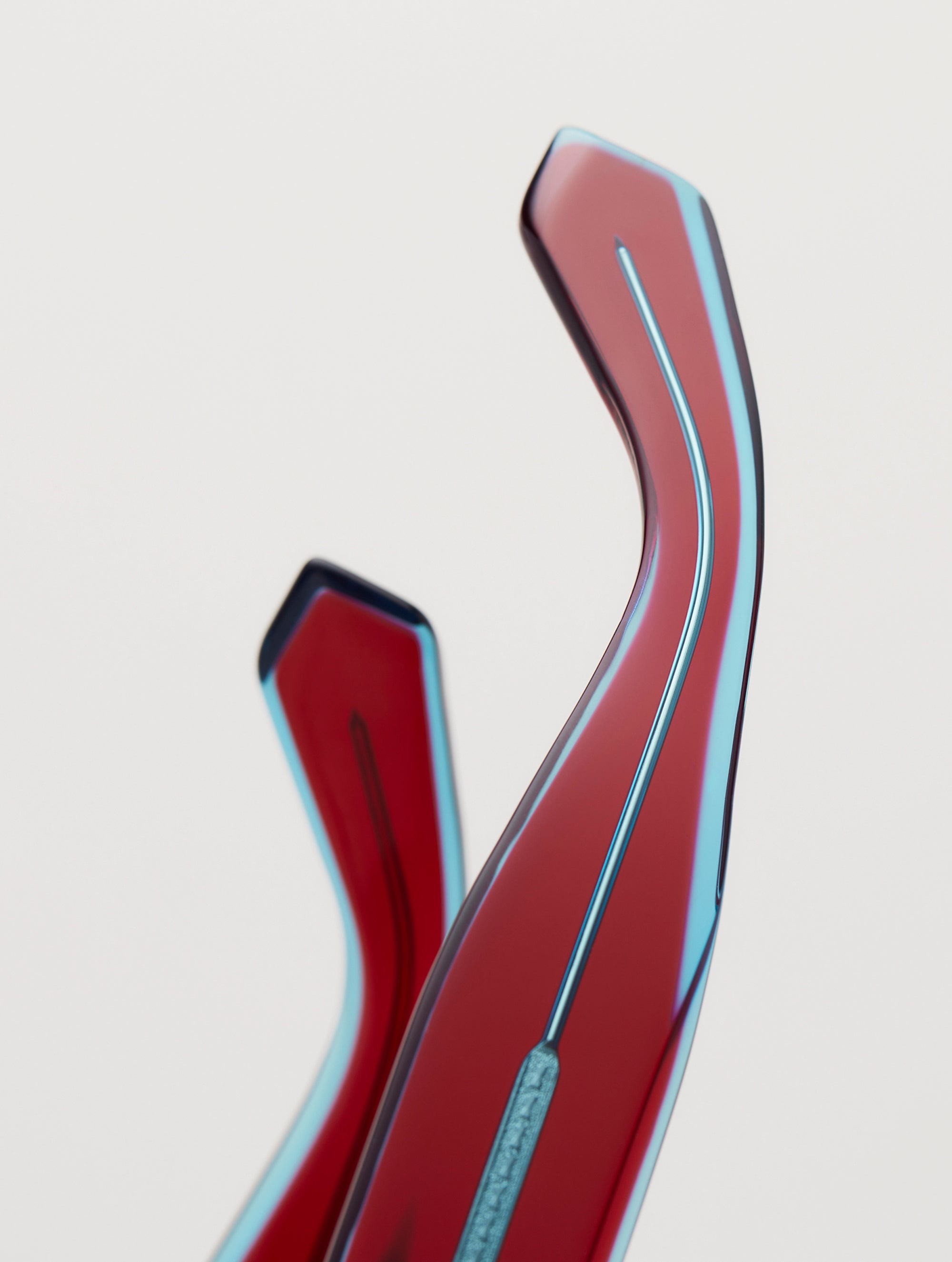

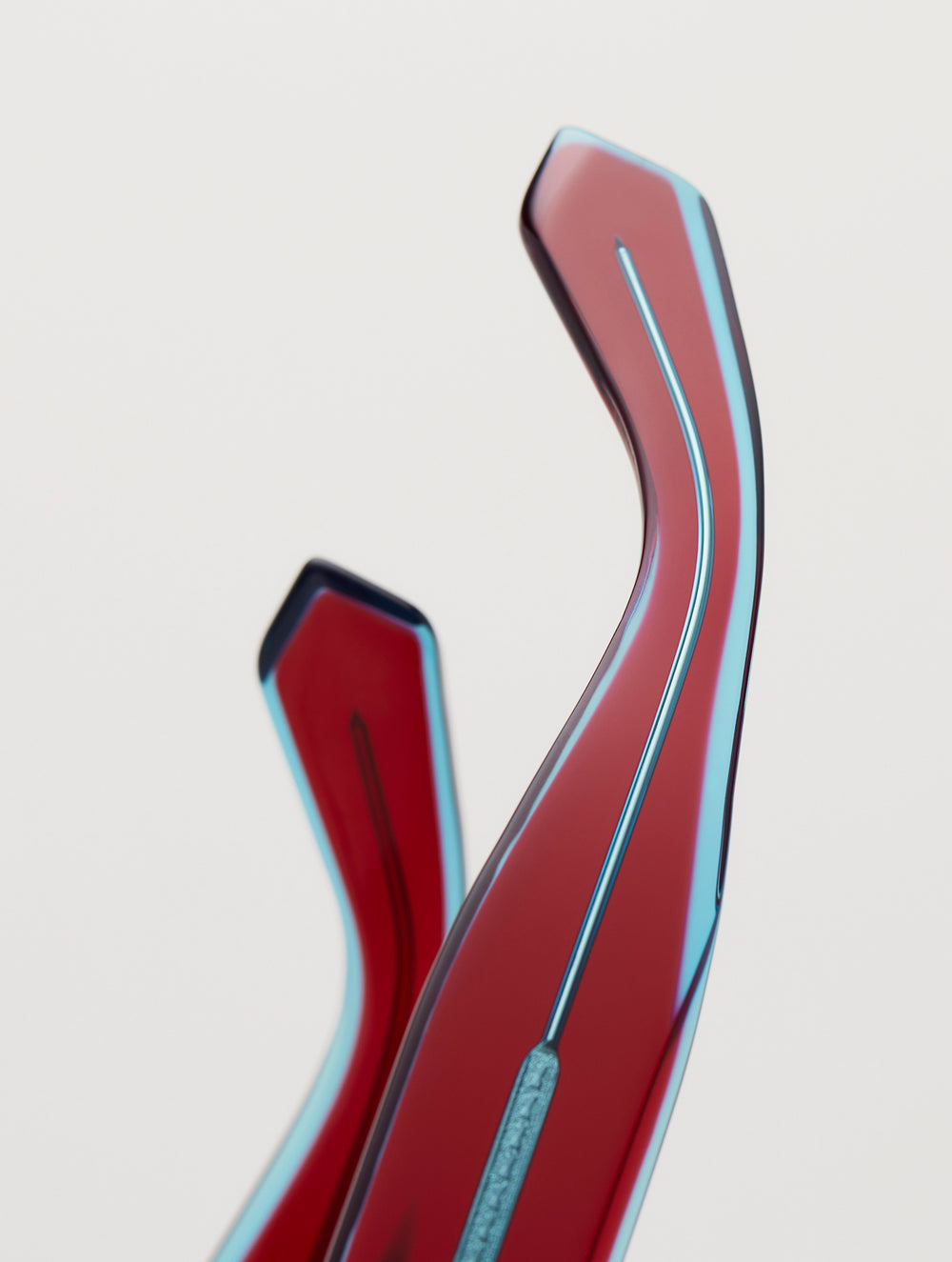

Drawing on Donald’s designs, we’ve created a series of frames based on a modular design. If you were to draw a line from lug to lug, temple tip to temple tip, you'd make a perfect square.

Acetate sheets in contrasting colours, carefully laminated to form a single layer. Colour – not as adornment – but as integral to the structure of the frame.

Acetate sheets in contrasting colours, carefully laminated to form a single layer. Colour – not as adornment – but as integral to the structure of the frame.

A limited run of five frames in five acetate encounters, handmade in our King's Cross workshop. Donald never made a pair of spectacles, but they might have looked something like this.

Edit: Untitled is now sold out. You can request for the frame to be remade through our Bespoke service.

Edit: Untitled is now sold out. You can request for the frame to be remade through our Bespoke service.